How would you send one hundred wedding invitations? - Keep your Product Backlog lean. Michał Piotrkowski

Envelope Stuffing Paradox

Imagine you are supposed to send one hundred wedding invitations. You have to prepare each invitation before you send it. Preparations include: folding the letter, putting it into the envelope, sealing the envelope, attaching the stamp. How would you approach that?

There are 2 obvious strategies:

- one by one (aka one-piece flow) - doing all actions for one invitation at a time and then proceeding to the next one,

- batching (aka mass production) - do one action for all the envelopes and then proceed to the next action.

Which one is more efficient? I bet, that if you asked this question, most people would answer without hesitation that the second method (batching) is quicker.

Apparently, it seems that it is not the correct answer. It is counterintuitive, as it may appear that the first strategy is more efficient. Weird, right? I have recorded a short video comparing those two approaches.

Also, there is a bunch of similar videos on Youtube. Check them out and, if you are still unconvinced, try to run the experiment yourself!

This phenomenon was described for the first time by James Womack and Daniel Jones in their famous book Lean Thinking. Explanation of this paradox lies in taking into account the time needed to switch the context and the handling of piling materials.

Nevertheless, time isn’t the biggest advantage of the one by one strategy. In this strategy, you get your first “complete” invitation after a few seconds which is great compared to the batching strategy in which you get your first “complete” invitation almost at the end of the entire “production” process (notice how this time grows with the increase of the number of invitations).

Imagine there is some kind of a gap in your assumptions. Sticking to our envelope example, let’s say that letters after folding do not fit the envelope. Now, the advantage of the one by one strategy seems more evident: you will detect “the error” quicker, you will have more time to resolve it, as well as, you won’t waste as many resources.

Envelope stuffing isn’t rocket science, there is not a lot of uncertainty about it. You may argue that, after careful analysis, you can anticipate all of the problems. However, there are industries (like startup industry) in which you can’t. The negative impact of work in large batches will be amplified in this kind of environments.

If you are interested in investigating this topic, I can recommend Eric’s Ries article: The power of small batches. The key lesson from this read is work in small batches.

Product Backlog Management

Forget the wedding invitations. Let’s get to the main topic of this article: How to manage your Product Backlog.

If I asked you what are the traits of a good Product Backlog you might answer that it should be complete, detailed, well organized, etc. However, in light of previous paragraphs, we see that creating big, detailed backlogs might not always be the best approach.

Big Backlogs means Big Batches.

Let’s have a look at some drawbacks of that.

Big Design Up Front

When you are creating detailed backlog beforehand aka BDUF (Big Design Up Front), it means that you are doing it when your knowledge about the product is minimal. You will never again know as little as at the beginning of the project about your users, their needs, how they are going to use your product, which ideas “work” and which ones don’t. Investing a lot of effort in creating fine-grained user stories with detailed, round descriptions of something that is just speculation is just a waste of resources.

Status Quo

You are less eager to update or drop user story that you have been describing for many hours. The more effort you put into creating your current Backlog the less likely you experiment and explore alternatives. A big pile of upcoming work will give the impression that everything is already decided and discourage creative thinking. What’s more, it can be intimidating for the team.

Maintenance

Once you have your 100+ stories in place, maintaining it becomes problematic. There is a higher chance that you start to shuffle stories back and forth so that the more urgent will be implemented earlier. The last but not least, navigating huge backlog is a nightmare. At some point, you stop seeing the forest for the trees.

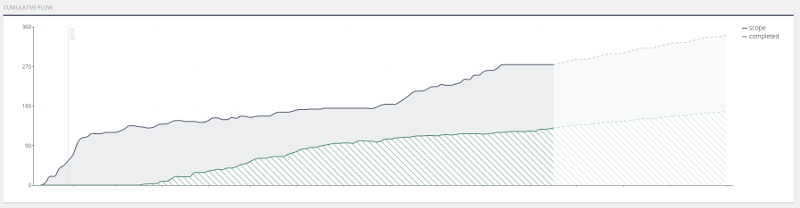

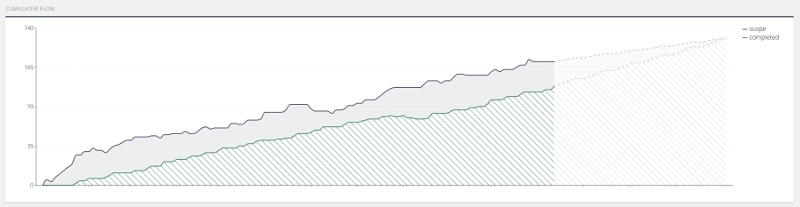

Take a look at these two figures below. These are screenshots of a cumulative flow diagram from two projects I have been participating in. The green area represents work that has been done, the greyish-blue one represents the remaining scope of the backlog.

The “Big” backlog

The “Big” backlog

The “Lean” backlog

The “Lean” backlog

In the first project, we experienced a lot of story reprioritization that postponed already delayed stories which effectively resulted in something that we called “user story graveyard”. We were reluctant to remove them entirely due to the effort we had put into creating them in the first place. Description of stories changed frequently and it was difficult to track all the important details in the avalanche of notifications. Effectively we spent a fair share of our time on “managing the backlog”.

When we were developing StoryHub.io (second screenshot) we tried to keep the backlog lean. We put detailed descriptions into the stories only if we were sure they would be implemented soon. Each story had its lifecycle. Usually, it started as a somewhat blurry and generic placeholder for a bigger epic. Over time it evolved into (usually multiple) more specific stories which ended up as a concrete, actionable tasks. We avoided any more detailed descriptions until the last phase.

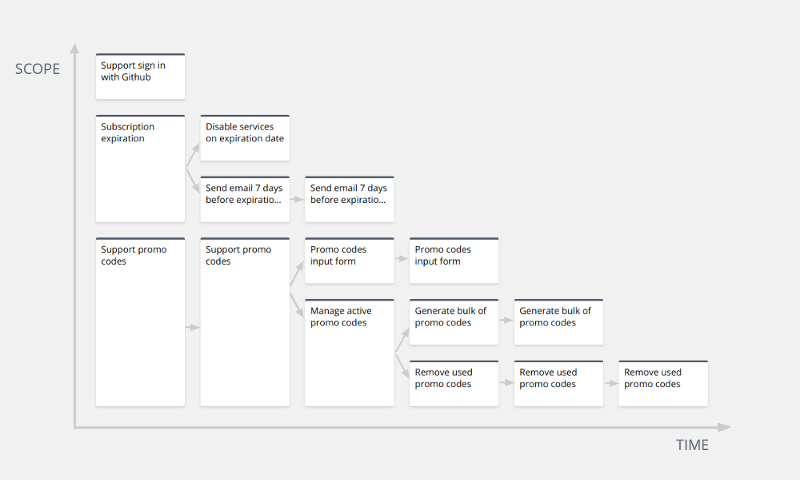

Just-in-Time requirements

This approach is commonly known as Just-in-Time requirements. The figure below shows a sample diagram that depicts this approach. Notice how at any point in time backlog remains small in the context of the number of stories. This results in a much lower overhead in the backlog management and also introduces better visibility (you can always fit the backlog on one screen) and higher predictability.

Backlog evolution with Just-in-Time requirements

Backlog evolution with Just-in-Time requirements

Summary

Too many stories in your backlog may hurt your performance. As in presented Envelope Stuffing Paradox, trying to analyze and define everything up front will likely lead to longer development time, as well as, more rework and waste.

To avoid this:

- Work in small batches, one piece at a time,

- Avoid premature analysis with Just-in-Time requirements,

- As a rule of thumb, it is always good to be able to fit the entire backlog on one screen.